Who's Who

,

Individual biographies tell the varied life stories of Gunzburg family members who, over the centuries, have lived lives as diverse as rabbis, merchants, bankers, painters, actors, oriental scholars, resistance fighters, adventurers, goldminers and monks, among others. Women have taken a front seat, each generation making notable contributions to the family’s story through their roles in passing on their maternal, cultural and philanthropic example.

The Gunzburgs’ world is much broader than just the family circle. Beyond its marital unions with other families, it embraces those who have kept close ties with the family as allies and colleagues, employees and protégés. The Gunzburgs are also linked to influential figures in the world of business, the arts and politics, not only in Russia and France but also in Switzerland, the United States and the United Kingdom, to name a few.

Happy and tragic, their wide-ranging destinies reveal from the 16th century to the present day a family’s extraordinary vitality and activity as fascinating actors over half a millennium of Western history, from the Iberian peninsula to the Russian Empire. Their life stories bear witness to the complex evolution of the Jewish world into the modern era and to the Gunzburgs’ involvement in the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment, and the evolving nature of modern judaism. They show how throughout the 19th century the Gunzburg family played a significant role in the economic development of the Russian Empire. In the face of the 20th century’s many ordeals – pogroms, revolutions, world wars, the Holocaust (the Shoah) – their biographies are works of memory to counter oblivion.

Alexandre de Gunzburg (dit Sacha) (24 avril 1863 Paris-28 juin 1948 Bâle)

Cinquième enfant d’Horace et d’Anna de Gunzburg, Alexandre était un membre éminent de la communauté juive de Saint-Pétersbourg avant la Révolution de 1917. Elevé d’abord à Paris, il a laissé d’intéressants mémoires sur la vie des Gunzburg dans l’hôtel particulier parisien du 7 rue de Tilsitt pendant le Second Empire et au début de la IIIe République. Passionné de géographie, il réalisa en 1878-1879 un voyage d’étude en Equateur pendant lequel il fit le don d’un sismographe moderne à l’Observatoire de Quito. A partir de 1881, Alexandre est établi à Saint-Pétersbourg où son père Horace a choisi de rapatrier toute sa famille. Il effectua comme officier son service militaire dans le régiment des Uhlans de Volhynie. En 1891, il épousa sa cousine Rosa Warburg, fille du banquier Siegmund Warburg et de Théophilia Rosenberg. Alexandre et Rosa s’installèrent dans un palais du 18e siècle à Saint-Pétersbourg au n°14 de la prestigieuse rue Millionnaïa. Ils en confièrent la réhabilitation à l’architecte décorateur Oscar Munts. Avec leurs sept enfants (Anna, Théodore, Olga, Véra, Marc – qui mourut en bas âge- Hélène et Irène), Alexandre et Rosa formaient une famille unie. De la période pétersbourgeoise, il existe un beau portrait à l’huile de Rosa de Gunzburg par Louise Abbema, conservé au Musée Carnavalet à Paris. Si la fortune et le confort mettent Alexandre de Gunzburg et les siens à l’abri des difficultés matérielles, les violences antisémites ne les épargnent pas : Alexandre fut blessé lors du pogrom de Kiev des 18-20 octobre 1905. Le récit qu’il a laissé de cet épisode constitue un témoignage historique de première main. Après la mort de son frère David en 1910, c’est Alexandre qui assuma les responsabilités communautaires et philanthropiques familiales. Avec sa femme Rosa, il pourvut aux besoins de l’orphelinat juif fondé par sa mère Anna. Il dirigeait aussi la firme familiale « J.E. Gunzburg » (mines d’or, assurances et compagnie de navigation). Lorsque la guerre éclate en août 1914, il était trop âgé pour être mobilisé. En octobre 1914, il participa à la fondation de l’EKOPO, Comité juif de secours aux victimes de la guerre, dont il était le président. Il se consacra à la correspondance internationale pour la levée des fonds, à la mise en œuvre des secours et à la coordination des 350 sous-comités et des diverses organisations. Il fut secondé dans sa tâche par son neveu Ossip de Gunzburg, réformé pour raisons de santé. Après la révolution de février 1917, Alexandre de Gunzburg soutint le gouvernement provisoire, se félicitant de la réalisation de l’égalité civile pour les juifs. Avec Boris Kamenka et Heinrich Sliozberg, il créa un Comité israélite pour propager l’emprunt Liberté et appella les communautés étrangères à souscrire. Sa fille Olga, infirmière, a fait partie d’une délégation désignée pour porter des cadeaux aux soldats sur le front. Son fils Théodore, jeune diplômé de la faculté de droit de Saint-Pétersbourg, est entré au service du nouveau gouvernement comme second attaché à la mission diplomatique envoyée à Washington. Le climat de lutte politique obligea bientôt Alexandre de Gunzburg à démissionner de ses fonctions alors qu’il s’opposait au courant anti-religieux qui divise désormais la communauté juive. Avec la prise du pouvoir par les bolcheviks le 25 octobre 1917 et la mise en place de la Terreur rouge, Alexandre et Rosa furent inquiétés par le nouveau pouvoir : leur maison est perquisitionnée, les affaires professionnelles sont suspendues, la gestion de l’orphelinat leur est ôtée et les membres de la famille doivent travailler manuellement pour obtenir leurs rations alimentaires. Au début du mois d’août 1918, Alexandre est arrêté par la Tcheka en tant qu’ancien officier de l’armée tsariste. Emprisonné à la prison de l’île de Kronstadt, au large de Petrograd, il fut libéré après de longues démarches réalisées par sa fille Olga. Grâce à un laisser-passer fourni par leur fille Anna, mariée depuis 1915 à Salomon Halpérin et établie à Kiev, Alexandre et Rosa, accompagnés de leurs filles Olga, Véra, Hélène et Irène, purent rejoindre Kiev, alors sous occupation allemande, puis partir pour Berlin le 7 décembre 1918. Après un séjour en Suisse, Alexandre et Rosa se sont installés à Paris où ils célébrèrent le mariage de leur fille Olga avec le banquier espagnol Ignacio Bauer en 1921. Mais Alexandre a la douleur de perdre sa femme Rosa le 17 février 1922. En 1923, leur fille Véra épousa Paul Dreyfus, banquier à Bâle. Par l’intermédiaire de son frère Pierre de Gunzbourg, marié à Yvonne Deutsch de la Meurthe, fille d’Emile Deutsch de la Meurthe, Alexandre se vit confier la direction de la Western Bank aux Pays-Bas : avec ses enfants les plus jeunes, Hélène et Irène, il s’établit donc à Amsterdam, où son fils Théodore vint le rejoindre. La menace nazie poussa Alexandre et les siens à un nouvel exil : après un passage dans le Sud de la France, Alexandre trouva refuge à Bâle où il mourut en 1948. Témoin d’une époque révolue, il a laissé de nombreux écrits qui constituent aujourd’hui des sources de grande valeur pour l’histoire de la famille Gunzburg.

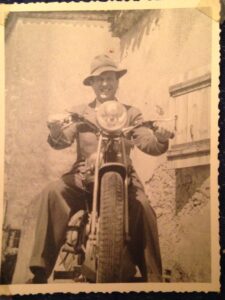

Alain de Gunzburg (19 January 1925, Paris–16 May 2004)

Alain de Gunzburg was the eldest son of the banker Jean de Gunzburg (1884–1959) and Madeleine Hirsch (1894–1979). A reserved businessman, he rarely spoke spontaneously about the dark years of the Second World War, in which he nevertheless distinguished himself as a young volunteer combatant in the Free French forces of General de Gaulle.

Alain was brought up conventionally with his brothers François (1927–1984) and Pierre (1930–2013) in the family home in Paris at 43 Avenue du Maréchal Fayolle in the 16th arrondissement. His maternal grandmother Alice Hirsch also lived with the family. In 1940, with the German invasion and occupation, his parents moved briefly to the Côte Basque, where Alain attended the lycée in Bayonne, then in Châtel-Guyon, not far from Vichy, France’s political centre at the time, where Alain passed his baccalauréat. His father Jean de Gunzburg, a naturalised Frenchman for many years and director of the Louis Hirsch & Cie bank, an institution of repute, did not imagine himself to be running any kind of risk. His brother-in-law and fellow banker, André Louis-Hirsch, who had been called up as an officer, was a prisoner-of-war in Germany at the time. But in the summer of 1941, after having protested unsuccessfully at the Aryanisation of their bank and at a time when Jews were being increasingly discriminated against and threatened in Marshal Pétain’s France, Jean and Madeleine de Gunzburg, their three children and Alice Hirsch managed to emigrate to the United States without falling foul of the widespread arrests and deportations. Before leaving France, they attempted to put the furniture and paintings of their Paris apartments out of harm’s way in a vault at the Banque de France and at the neighbouring Argentine embassy, but all their property was stolen by the Nazis, with the French administration’s approval.

On 19 June 1943, his eighteenth birthday – he was already a student at Harvard University – Alain signed his enlistment papers for what were then known as the Fighting French Forces (Forces Françaises Combattantes). Leaving New York by ship on 13 August 1943, he arrived at Bristol, England on 28 August. On 13 September he was assigned to the Ecole des Cadets de la France Libre, a school that had been established by de Gaulle as the equivalent of the prestigious French officers’ school at Saint-Cyr. At Ribbesford House, volunteers of all kinds of origins and antecedents were trained together in conditions of strict discipline. Rather than the clandestine action he had dreamed of when he enlisted, Alain found himself following a complete officer cadet course (mathematics, history, geography, Morse code, mine-clearing, topography, intensive physical training). He formed a close bond with Jean Géraud-Vinet, who had come directly from Madagascar to London. Ranked 49th out of 150 cadets in the final examination of the “class of 18 June”, he was disqualified from his first choice of the air force by his poor eyesight, and at his passing-out parade, presided over by General Koenig, he chose the army. On 28 July 1944 he was appointed liaison officer to the 2nd Armoured Division led by General Leclerc and to US Army. He took part in the campaign to liberate France (“the Royan operations”) and then the German campaign, notably the liberation of Dachau concentration camp, as far as Berchtesgaden (Hitler’s outpost of the German Chancellery). His admirable command of English and knowledge of American culture made him a highly valued liaison officer. France awarded him the “Médaille commémorative française de la guerre 1939–1945”, with bars reading “Volunteer”, “Liberation” and “Germany” (“Engagé volontaire”, “Libération”, “Allemagne”). The US government awarded him the Presidential Unit Citation.

After the war Alain was keen to turn the page on his demanding wartime service. He resumed his studies at Harvard Business School and earned an MBA (Master of Business Administration). In 1953 he married Aileen Mindel (Minda) Bronfman (1925–1985), a young Canadian whose father Samuel, a great philanthropist and early champion of the state of Israel, headed the firm of Seagram, a small company specialised in the production and wholesaling of alcoholic spirits that he built up substantially. Although Alain was strengthening his ties with north America, he nevertheless chose to settle in Paris, in Avenue Bugeaud, faithful to the way of life he had inherited from parents and grandparents. His wife Minda, with a degree in history and political science from Columbia University, gained a Master’s in history of art at the Sorbonne and founded the Association de soutien et de diffusion d’art (ASDA) (Association for the support and promotion of art), with branches in Paris, Washington and Montreal, to encourage research into art and the history of art; she also organised respected lecture series by art historians in Europe and the USA. She also started to build up a personal art collection that became notable for its works by American abstract expressionists.

Alain was a managing partner for the family bank of Louis Hirsch & Cie from 1954 to 1966, orchestrating its merger with Seligman’s and then the Louis Dreyfus bank, before the banking group was sold to Groupe Bruxelles Lambert in 1980. At the request of his father-in-law, who was interested in the French wine market, Alain made investments in the champagne houses of Mumm and Perrier-Jouët and the Bordeaux négociant Barton et Guestier. Wanting to develop the presence of these companies in the international market, he took over the running of G. H. Mumm & Cie in 1973, concentrating on the promotion of its famous “Cordon Rouge” bottle. To commemorate his wife Minda, who had died from cancer in 1985, Alain gave several of her artworks to the Musée du Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay and founded the prestigious Minda de Gunzburg Prize, for the best art exhibition catalogue. In memory of their mother her sons Charles and Jean de Gunzburg also created the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard University. Alain remarried in 1990 to Françoise Gérald.

Alexandre de Gunzburg (“Sasha”) (24 April 1863, Paris–28 June 1948, Basel)

The fifth child of Horace and Anna de Gunzburg, Sasha de Gunzburg became the head of the Jewish community of St Petersburg before the Russian revolution of October 1917. He was the author of a memoir of the lives of the Gunzburgs in Russia and France.

As a child growing up in Paris, Sasha was taught at home alongside his brothers, sisters and cousins in their own classroom in the town house at 7 Rue de Tilsitt. Their teachers were Robert Rohmann, an engineer from Odessa (head tutor), Jules Labbé (French, history and classics), Nicolas Minsky-Vilenkine (Russian), Madame Delaporte (rhetoric), Ivan Pokhitonoff (Russian and mathematics), Jules Massenet (music), Adolphe Neubauer and Rabbis Kirsch et Zadok Kahn (religious education). In 1878–1879 Sasha’s interest in geography led him, at the age of fifteen, to make a study trip to Ecuador, where he donated a modern seismograph to the observatory at Quito. From 1881 he lived in St Petersburg, where his father gathered all his children around him. After completing his military service in a regiment of uhlans in Volhynia, in 1891 he married his cousin Rosa Warburg, daughter of the the banker Siegmund Warburg and Théophile Rosenberg. After their wedding Alexandre and Rosa moved into an 18th-century palace at 14 Millionaya Street, which they renovated with the help of the architect Oscar Munts. They had seven children: Anna (b.1892), Theodore (Fedia) (b.1893), Olga (b.1897), Véra (b.1898), Marc (b.1903) – who died in infancy – Hélène (Lia) (b.1906) and Irène (b.1910).

On a journey to Kiev (Kyiv) to attend the burial of his maternal grandmother Eleone (Elka) Rosenberg, Sasha was wounded in the pogrom of 18–20 October 1905. After his brother David’s death in 1910, he took over the family’s community and philanthropic responsibilities, and along with his wife Rosa managed the Jewish orphanage which his mother had founded. He also ran the family business of J. E. Gunzburg (goldmines, sugar, forestry, insurance and a shipping company).

When Russia entered the war in August 1914, Sasha was over the age for mobilisation and instead he devoted himself to the welfare of Jewish communities in combat zones. From October 1914 he oversaw EKOPO, the Jewish Committee for Aid to War Victims (especially its international fundraising efforts, and the delivery of aid and co-ordination of sub-committees and other organisations). He was supported by his nephew Osip de Gunzburg, exempted from military service on health grounds. After the February 1917 revolution he backed the provisional government, taking satisfaction in the achievement of civil equality for Jews. He, Boris Kamenka and Heinrich Sliozberg formed a committee to promote vigorously subscription to Liberty bonds, calling on communities abroad to subscribe. His daughter Olga, a nurse, was a member of a Jewish delegation that distributed gifts to soldiers at the front, and his son Fedia, who had graduated from the law faculty at St Petersburg, was appointed second secretary to the diplomatic mission to Washington. Politicking in the Jewish community forced Sasha to resign his role as leader after he publicly attacked an anti-religious tendency that was splitting community authorities.

When the Bolsheviks seized power on 25 October 1917 and the Red Terror began, Alexandre and Rosa were considered to be “enemies of the people”. Their house was confiscated, they were banned from conducting business and excluded from running their orphanage, and their family had to do manual labour to obtain food rations. In early August 1918, Sasha was arrested by the Cheka as a former officer in the Tsar’s army. Imprisoned in Kronstadt on Kotlin island, west of St Petersburg, he was freed after lengthy efforts by his family and friends, and thanks to a laissez-passer provided by his daughter Anna, who in 1915 had married Salomon Halperin and settled in Kiev, Sasha and Rosa and their daughters Olga, Véra, Hélène and Irène were able to reach Kiev, then under German occupation, and subsequently leave for Berlin in December 1918. After a stay in Switzerland, Sasha and Rosa settled in Paris where their daughter Olga married a Spanish banker, Ignacio Bauer, in 1921. Rosa died on 17 February the following year. In 1923 Véra married Paul Dreyfus, a banker from Basel. With the help of his brother Pierre de Gunzbourg, married to Yvonne Deutsch de la Meurthe, daughter of Emile Deutsch de la Meurthe, Sasha was appointed to run the Western Bank in the Netherlands, and with his two youngest children, Hélène and Irène, he settled in Amsterdam. Fedia later joined them there. Hélène married Alexandre Berline, who was also from St Petersburg, and Irène married Bob de Vries. Fedia married Wilhelmina Ptasznik. Within a few years the Nazi threat impelled Sasha and his family to seek a new exile: after a short stay in the south of France he found refuge in Basel, where he died in 1948. Witness to an era of turmoil, he left behind a valuable collection of memoirs. An oil portrait of Rosa de Gunzburg by Louise Abbema hangs in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris.

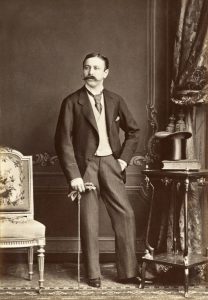

Alexandre Süsskind de Gunzburg (15 April 1831, Orsha–9 or 10 December 1878, Naples)

The eldest child of Joseph Evzel de Gunzburg and Rosa Dynin, Alexandre de Gunzburg was known for his high-spirited personality. As a mischievous boy, he once used sealing wax to glue his Talmudic teacher’s beard to his desk as he dozed. Married to Rosalie Ettinger, he had two sons, Michel (b.1851) and Jacques (b.1853), both born at Kamenets-Podolsk where the Gunzburgs had their trading agency and Alexandre worked for the family firm, centred round its concession for the production and sale of alcohol. Alexandre had an imposing physique and was well known for standing his ground in the face of anti-Semitic attacks, but he was especially noted for his enjoyment of cards and women.

In 1857 he moved to Paris with his family at his father’s invitation. From the 1860s onwards he lived apart from his wife, and for a time was the lover of the actress Sylvia Asportas, whom he showered with an apartment, horses and a carriage, and the latest fashions. Having squandered his fortune, Alexandre felt the full weight of his father’s disapproval: Joseph Evzel refused him a partnership in the Gunzburg bank (founded in 1859 in St Petersburg – his brothers Horace, Ury and Salomon all became partners) and disinherited him. When their father died in 1878, Horace sought out his brother in Italy, where he had gone to live, to sign a family agreement that softened the harsh conditions imposed by Joseph Evzel and provided Alexandre with a pension of 6000 francs a month. Shortly after his meeting with his brother, however, Alexandre died suddenly in Naples. He is buried in the family vault at the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris. His younger son Jacques became a well-known banker and the father of Nicolas “Nicki” de Gunzburg, the actor and later celebrated editor of Vogue.

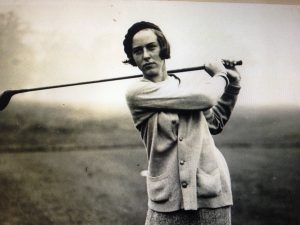

Aline de Gunzbourg (4 January 1915, London–25 August 2014, London)

The fourth child of Pierre de Gunzbourg and Yvonne Deutsch de la Meurthe, Aline grew up in Paris at 54 Avenue d’Iéna, in an apartment owned by the Deutsch de la Meurthe family. Emile Deutsch de la Meurthe was the founder, with his brother Henry, of the Jupiter oil company which subsequently merged with Shell France; the family lived in considerable luxury, which included having their own private petrol pump to refuel the family’s vehicles. Aline developed an early talent for golf, and her parents not only took her to North Berwick in Scotland for her summer holidays, where she played golf morning and afternoon, but had a house built at Garches, next to the Saint-Cloud golf course. Coached by the best professionals, including George Duncan, in 1934 Aline won the French women’s championship.

Her early life was marked by grief: her sister Béatrice died in 1925 in a riding accident, and her brother Cyrille died on military service with the Chasseurs Alpins, France’s mountain infantry force, in 1932. In 1934 Aline married André Strauss, son of the art collector Jules Strauss, with whom she had a son Michel in 1936, but only three years later André died of cancer.In June 1940, at the defeat of France by Nazi Germany, Aline decided the family should take refuge in the south of France, first at Antibes then at Cannes. However, shocked by the anti-Semitic mood she encountered there, and aware of the danger her family faced, she approached the US diplomatic representatives and French authorities at both Vichy and Nice, and on New Year’s Day 1941 left France with her son Michel, travelling to Spain and Portugal and from there by sea to New York. Three months later, her parents joined her. In Paris the German administration not only looted the family’s property but installed the Nazi unit in charge of the organised plunder of Jewish property (Möbel Aktion) at 54 Avenue d’Iéna. Throughout the war, Aline managed to remain in touch by letter with her brother Philippe, who had organised a resistance network in the south Dordogne and Lot-et-Garonne for the British Special Operations Executive. In 1943 she married Hans Halban, an Austrian nuclear physicist who subsequently became French and had arrived in Montreal from England in 1942 to head a team as part of the allied wartime nuclear research effort; she and Hans had two sons, Pierre (known as Peter), born in New York in 1946, and Philippe, born at Oxford in 1950. At the war’s end Aline returned to Europe, not to France but to Oxford where Hans Halban was invited by Frederick Lindemann (Lord Cherwell) to lead a team at the Clarendon Laboratory at Oxford University. Aline and Hans divorced in 1955. Hans was invited back to France where he directed setting up the Saclay Nuclear Research Centre (CEA), and in 1956 Aline married the philosopher and historian of ideas Isaiah Berlin, whom she had met in New York. At the end of her life, Aline’s portrait was painted by Lucian Freud.

Anna de Gunzburg (10 March 1838, Haiffin Podolia –9 December 1876, Paris)

The daughter of Eleone Gunzburg and Hessel Rosenberg and the wife of Horace de Gunzburg, Anna was a leading light in the Gunzburg family’s social rise in the mid-19th century. As a child growing up in Podolia in the Russian Empire, she received a thorough education, and when, having spoken French from a young age, she came to Paris in 1857 with her parents-in-law Jospeh Evzel and Rosa de Gunzburg and all their children, she became the linchpin of the Gunzburg family’s social acceptance.

Her good looks, intellectual qualities and grace were widely admired, and as mistress of a distinguished household she was frequently mentioned in the Parisian society columns whenever her father-in-law gave a ball. Anna was particularly attentive to the interior decoration of the town house at 7 Rue de Tilsitt, and her curiosity and sensitivity attracted many artists, among them Léon Bonnat, Auguste Ricard and Mihàly Zichy; the sculptor Mark Antokolsky; and composers Camille Saint-Saëns, Jules Massenet and Modest Mussorgsky. She also founded a Jewish orphanage in St Petersburg. She was a devoted mother on one occasion not hesitating to decline a dinner invitation at the imperial court of Napoleon III to stay at home with her children. She followed their education closely, often attending their lessons with them. Her death in childbirth with her eleventh child plunged the Gunzburg family into deep grief. Through her brothers and sisters, who made matrimonial alliances throughout Europe, Anna counted many distinguished families among her circle of friends: the Ashkenazys and Brodskys in Russia, the Warburgs and Hirsch-Gereuths in Germany, the Hertzfelds in Hungary. Anna de Gunzburg was painted several times by Edouard Dubufe, Auguste Ricard and Léon Bonnat, and Marc Antokolsky sculpted a bust of her.

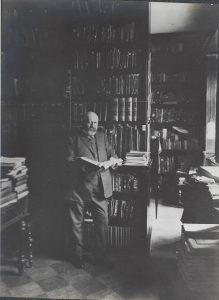

David de Gunzburg (5 July 1857, Kamenets-Podolsk–22 December 1910, St Petersburg)

A respected orientalist and bibliophile, David de Gunzburg devoted his career to promoting Judaism as a Hebrew and Talmudic scholar, community leader and defender of the rights of Jews in the Russian Empire. His exceptionnal studious character was evident in his early childhood and his parents, Horace de Gunzburg and Anna Rosenberg (he was their second child), and his grandfather Joseph Evzel were all deeply proud of him. Joseph Evzel made the family home at 7 Rue de Tilsitt in Paris a centre for the promotion of Jewish culture, and David’s scholarly leanings were encouraged by introducing him to experts and intellectuals such as Senior Sachs, the Gunzburgs’ librarian, and Adolf Neubauer. In 1875, when he was eighteen, he became a student at the University of St Petersburg’s school of oriental languages under Baron Victor Rosen. Besides Hebrew, David studied Arabic, Syrian, and Russian literature. In the winter of 1878 his father asked him to accompany his brother Marc, ill with tuberculosis, to Madeira, where Marc died on 22 December. Having completed his military service with a regiment of uhlans at Łomza in Poland, David continued his orientalist studies with Stanislas Guyard, Arab and Persian tutor at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris, and Wilhelm Ahlwardt, Arab literature specialist at Greifswald, Germany. In the summer of 1883 he set out on a six-month study trip to the Caucasus, where he learnt Armenian and Georgian. (By the end of his life he spoke twenty languages.) Returning to Paris, on 18 December 1883 he married his cousin Mathilde de Gunzburg at the rue de la Victoire synagogue. The couple settled in St Petersburg, but having grown up in Parisian high society, Mathilde found it hard to adapt to the less liberal traditions of Russian Judaism. The couple had five children: Anna (b.1885), Osip (b.1887), Marc (b.1888), Sonia (b.1890) and Eugène (b.1890). Osip, who suffered from nervous disorders, was a constant source of worry; Marc, like his uncle Marc before him, sadly also died of tuberculosis, at Menton in 1891. In 1898 David bought a house on the other side of the Neva, on Vasilyevsky Island, line 1, no. 4, near the university, where he kept his library, one of the most remarkable in Europe with 35,000 volumes of manuscripts, rare editions and incunabula.

David de Gunzburg’s main works are an edition of the Tarshish of Rabbi Moses ibn Ezra (Berlin, 1886) and Le Divan d’Ibn Guzman, Texte, traduction, commentaire (Berlin, 1896). With the historian and art critic Vladimir Stasov he published L’Ornement hébreu (Berlin, 1905). He wrote a series of articles on biblical metrics, notably Monsieur Bickell et la métrique hébraïque (Paris, 1881) and published essays in the anniversary anthologies of his fellow scholars Khvolson, Rosen, Garkavi, Zunz and Steinschneider. He contributed to the Revue des Etudes juives, Revue critique, Voskhod, Ha-Yom, Ha-Melitz and Journal du Ministère de l’Instruction publique de Russie (about the first Jewish school in Siberia). In association with Rabbi Lev Katznelson, David initiated and financed the Evreyskaya encyclopedia (Jewish Encyclopaedia) published by Brockhaus and Efron between 1908 and 1913, to which he also contributed. He was a member of the Society for Oriental Studies (Russia), the Scientific Committee of the Russian Department of Public Instruction, Archeological Society of St Petersburg, Société asiatique de Paris and the Société des études juives à Paris, which he co-founded. In 1908 he was allowed to found an Academy of Oriental Studies and Judaism in St Petersburg, a private free educational centre for professors and students who had been driven out of the university.

David did not devote his life exclusively to his studies: alongside his father Horace he also worked for the Gunzburg bank until its failure in 1893, for the Gunzburg trading agency, and for the family’s sugar refinery at Mohilna in Podolia.

David was a leading authority in the intellectual, spiritual and philanthropic circles in the Jewish community in Russia. He kept open house in St Petersburg and at Mohilna for all those seeking material or legal support. Like his father Horace, he was active in the Society for Agricultural and Artisanal Labour (ORT) and the Society for the Promotion of Culture (OPE). In St Petersburg he founded the Society for Aid for Jews in Need and the Maakhol Kosher Society for Jewish Students. As a strong advocate for the development of agricultural skills in the Jewish population, he supported the establishment of a Minsk agricultural college and the agricultural college of Novopoltava in Kherson district. From 1893 onwards he chaired the central committee of the Jewish Colonisation Association in St Petersburg, and in Santa Fe province in Argentina a Jewish settlers’ village was named “Baron de Gunzburg”. With his father Horace, David was also a member of the Union for Equal Rights, which campaigned for votes for all subjects of the Emperor in the Duma elections after the revolution of 1905. He was a leading voice in denouncing the pogroms and active in delivering aid to the victims. In January 1906 he was appointed, along with Marc Varshavsky and Heinrich Sliozberg, to an enquiry to determine the needs of victims of the pogrom of Hormel, and he led a delegation to Minister Witte to demand the imperial administration take steps to end anti-Semitic violence. The Jewish community’s appeal went unheard. After the Białystok pogrom of 14–16 June 1906, David went to organise the aid effort in person with David Feinberg. In 1909 he became one of the representatives of the permanent commission for Jewish affairs set up by Jewish communities.

In 1910, at the age of fifty-three, a year after his father, David died of cancer. In contrast to the other members of his family laid to rest in the family vault of the cemetery of Montparnasse in Paris, he chose to be buried in the Jewish cemetery in St Petersburg.

After her husband’s death Mathilde de Gunzburg began the process of selling his library to the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, but the First World War and 1917 revolution prevented the sale taking place. Nationalised by the Bolsheviks, the library today is partly conserved in Moscow’s national library as the “Gunzburg Library”. The text of the Haggadah shel Pesach is known as the “Gunzburg Haggadah”. David de Gunzburg’s personal archive is conserved at the Russian national library in St Petersburg.

Dimitri de Gunzburg (“Berza”) (13/25 October 1870, Lausanne-Ouchy–declared missing in 1918, Caucasus)

The eighth child of Horace de Gunzburg and Anna Rosenberg, Dimitri de Gunzburg lived the life of a dandy, dividing his time between St Petersburg, Paris and London.

Known by his family and friends as Berza (a nickname given him by his Breton governess), he had a childhood marked by the death of his mother when he was only six years old. As a young man he rebelled against his father’s seriousness with his careless manners and taste for extravagance and high jinks. Developing a love of art and antiques, in 1907 he married Guétia Brodsky, daughter of the famous sugar magnate, but almost immediately abandoned married life, without his young wife holding it against him.

After his father’s death in 1909, bolstered by his financial independence, he became a friend and associate of Serge Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes. As “director-administrator” of the famous ballet company, Dmitri both acted as treasurer and took an active role in mounting its shows. The dancer Nijinsky wrote in his journal that “the baron de Gunzburg is a good man” and “an artistic amateur and costume designer of great talent”. His sketches of his journey to Egypt inspired the sets and costumes of Michel Fokine’s ballet, Nuit d’Egypte. In 1913, when Diaghilev withdrew at the last moment from a tour of South America with L’Après-midi d’un faune, he entrusted the company to Dimitri. The First World War interrupted the Ballets Russes’ touring, and Dimitri enlisted in 1916 in the imperial Russian army, joining the “Savage Division”, a cavalry division composed mainly of Muslim volunteers from the Caucasus. His choice was probably influenced by his liking for the division’s Caucasian uniform, which caused a sensation when he wore it in St Petersburg. Sent on a mission to the Caucasus, he disappeared there in 1918 in unknown circumstances, at the height of the civil war provoked by the Bolshevik revolution the year before. The accounts of the Ballets Russes that Dimitri left behind were so muddled that Diaghilev found himself having to pay bills every time he passed through Paris for several years afterwards. No one knows what became of the art collections Dimitri left in his apartment in St Petersburg, among them busts by Antokolsky of Horace and Anna de Gunzburg and an unsigned portrait of his great-grandfather Gabriel de Gunzburg (1793–1853) which he had inherited.

Dimitri de Gunzburg (“Berza”) (13/25 October 1870, Lausanne-Ouchy–declared missing in 1918, Caucasus)

The eighth child of Horace de Gunzburg and Anna Rosenberg, Dimitri de Gunzburg lived the life of a dandy, dividing his time between St Petersburg, Paris and London.

Known by his family and friends as Berza (a nickname given him by his Breton governess), his childhood was marked by the death of his mother when he was only six years old. As a young man he rebelled against his father’s seriousness with his careless manners and taste for extravagance and high jinks. Developing a love of art and antiques, in 1907 he married Guétia Brodsky, daughter of the famous sugar magnate, but almost immediately abandoned married life, without his young wife holding it against him.

After his father’s death in 1909, bolstered by his financial independence, he became a friend and associate of Serge Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes. As “director-administrator” of the famous ballet company, Dmitri both acted as treasurer and took an active role in mounting its shows. The dancer Nijinsky wrote in his journal that “the baron de Gunzburg is a good man” and “an artistic amateur and costume designer of great talent”. His sketches of his journey to Egypt inspired the sets and costumes of Michel Fokine’s ballet, Nuit d’Egypte. In 1913, when Diaghilev withdrew at the last moment from a tour of South America with L’Après-midi d’un faune, he entrusted the company to Dimitri. The First World War interrupted the Ballets Russes’ touring, and Dimitri enlisted in 1916 in the imperial Russian army, joining the “Savage Division”, a cavalry division composed mainly of Muslim volunteers from the Caucasus. His choice was probably influenced by his liking for the division’s Caucasian uniform, which caused a sensation when he wore it in St Petersburg. Sent on a mission to the Caucasus, he disappeared there in 1918 in unknown circumstances, at the height of the civil war provoked by the Bolshevik revolution the year before. The accounts of the Ballets Russes that Dimitri left behind were so muddled that Diaghilev found himself having to pay bills every time he passed through Paris for several years afterwards. No one knows what became of the art collections Dimitri left in his apartment in St Petersburg, among them busts by Antokolsky of Horace and Anna de Gunzburg and an unsigned portrait of his great-grandfather Gabriel de Gunzburg (1793–1853) which he had inherited.

Guy de Gunzburg (1 January 1911, Paris–16 January 2006, Miami)

Guy de Gunzburg was the son of Robert de Gunzburg and Lucie Deutsch de la Meurthe. A French-American businessman, he left behind memoirs about both his family and the early years of the Second World War.

Guy had a comfortable childhood growing up with his sister Monique (1913–2011) and brothers Alexis (1917–1991) and Yves (1920–1945). In their town house at 25 Avenue Bugeaud (today’s Avenue Hubert-Germain) in the 16th arrondissement in Paris, parents and children lived strictly separate existences. Their upbringing was entrusted to the care of an English nurse, Nana Baker, assisted by her sister Molly. Every Thursday they would have their lunch with their paternal grandmother, Henriette de Gunzburg, the widow of Salomon de Gunzburg, the banker. Their mother, egocentric and passionate about her Pekinese dogs, never came up to the children’s floor. Their father would sometimes put in an appearance to make sure they were doing their homework.

Educated in France and then at Le Rosey at Rolle in Switzerland, Guy went on to study at France’s Ecole libre des sciences politiques (Sciences Po). After military service in the artillery at Châlons-en-Champagne, he worked for two years in the French offices of Shell and then at the associated SOGIP (Société de gestion d’intérêts privés), a “family office” dedicated to the interests of the Deutsch de la Meurthe family. He married Jacqueline Léopold, the sister of his friend Roger Léopold with whom he had formed a close bond during military service. Their son Jean-Louis was born in 1935. The following year, as Hitler remilitarised the Rhineland in violation of the treaties of Versailles and Locarno, Guy was briefly recalled to his regiment before being demobilised. He then worked as managing director of a company importing maté from Brazil to Europe and north Africa, the Companhia d’Expansão do Maté, set up in 1937 by Pierre de Fleurieu and in which his father Robert had a stake. He initially hoped to build it into a valuable import-export business between south America and Europe, but the reality of the political situation in Europe had impressed itself on him and, having read Mein Kampf and watched Germany’s huge rearmament programme, he chose instead to improve his military training, taking courses in radio operation and military English.

In August 1939 he decided to send his wife and their son Jean-Louis and newborn daughter Eliane and her nurse to Saint-Lunaire, near Dinard in Brittany, where his parents had rented a villa. While he was there, on 2 September, he got his mobilisation orders as a non-commissioned officer responsible for liaison and interpreting in the Douai region in the north of France, between French forces and a British light artillery regiment which he accompanied to Belgium in spring 1940. During this “phoney war” period, Guy’s wife Jacqueline and sister Monique Leven were busy setting up a military hospital at Deauville, assembling equipment and recruiting medical staff – a substantial achievement, but a facility that would never be used…

In June 1940 as the German offensive advanced, French civilians fled south. On 17 June Marshal Pétain, head of the French state, gave the order to stop fighting. The army was ordered to withdraw to the west and the sea. A witness to the drama of the difficult evacuation around Dunkirk, Guy was one of those who managed, against the odds, to escape capture. Having withdrawn to Bray-les-Dunes, a small town emptied of its residents, the hungry and weakened soldiers of Guy’s regiment worked on to destroy the equipment they were about to abandon to stop it falling into the Germans’ hands. Having reached Dunkirk with difficulty, Guy succeeded in finding a space on a destroyer. Evacuated to Dover, for several days he was detailed to receive the French troops arriving from Dunkirk and dispatch them to trains waiting to take them on to the southern English ports from where they would return to France. One of those he came across in these chaotic and tragic circumstances was his friend Guy de Rothschild.

Repatriated to France at Bayonne, Guy was able to join up with his family, who had retreated to their villa at Biarritz. There he learned that his friend Alexis de Gunzburg (1917–1991) was a prisoner of the Germans while his brother Yves (1920–1945), just turned twenty, had volunteered to join General de Gaulle’s Free France, leaving from St-Jean de Luz where he joined up with a group of Polish soldiers ready to embark. At Biarritz Guy and his family made themselves useful receiving refugees and setting up a soup kitchen. Soon, however, their home at Villa Elhorria was requisitioned to become the Germans’ general headquarters and residence of General von Rundstedt, whom Hitler had put in charge of the coastal defence. All too aware of Vichy’s regime of collaboration and its anti-Semitic policies, the Gunzburgs departed towards the Côte d’Azur.

Subsequently, after a circuitous journey through Spain and Portugal, Guy’s parents Robert and Lucie de Gunzburg managed to reach New York, where Robert died of a heart attack in 1943, inconsolable at having left France and his children. Guy had his own difficulties in making his escape from France, but was helped by a false document certifying that he belonged to the Russian Orthodox faith, and thanks to his Franco-Brazilian import-export company he was able to get a visa for Brazil in May 1942. He would not see his brother Yves again, who fell in combat on 30 January 1945 at Elsenheim during the hard fighting to liberate Alsace, after having spent a large part of the war in Africa in the French Foreign Legion. Guy himself spent four years in Brazil at Copacabana in Rio de Janeiro and subsequently became an American citizen. In New York in 1947 his family grew with the birth of Gérard, his third child. Guy liked to sculpt, draw, and spend time at his farm at Spottswood in Virginia, where he bred Black Angus cattle. He wrote valuable memoirs about his youth and war years: “Forgotten Dunkirk” (“Dunkerque oublié”) and “Souvenirs of my childhood” (“Quelques souvenirs de mon enfance”). He died on 16 January 2006 in Miami in Florida.

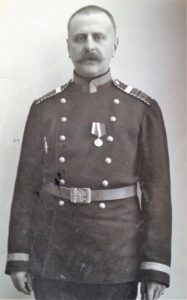

Jacques de Gunzburg (20 November 1853, Kamenets-Podolsk–28 January 1929, Paris)

Jacques de Gunzburg was a renowned international banker. The second son of Alexandre de Gunzburg (1831–1878) and Rosalie Ettinger (1829–1897), Jacques spent his first four years in Kamenets-Podolsk before moving to Paris where his grandfather Joseph Evzel had settled with his family in 1857. His parents were not close to each other and quickly led separate lives. In contrast to his father Alexandre, whose careless behaviour aroused paternal disapproval, Jacques showed himself a worthy heir to Joseph Evzel and was his favourite grandson. With a science degree from the University of Poitiers, Jacques began working for the Gunzburg trading agency and the family bank, spending lengthy periods in Russia. While he was there he completed his military service in the imperial Russian army, just as Joseph Evzel succeeded in persuading the tsarist administration to pass a law that included Jews in the obligation for military service. After first joining the Narva lancers in Vilna as a volunteer, Jacques joined a model squadron in St Petersburg, where, at the razvod (the annual military ceremony), Tsar Alexander personally congratulated the excellent officer cadet. Jacques later took part in the Turkish campaign of 1877–78 and was “decorated, for personal deeds in combat with the enemy, with the Order of St Stanislas with Sword”.

After nearly a decade of military service, Jacques returned to France and the Paris branch of the Gunzburg bank, where he worked until the bank’s failure in 1893. After a stay in London, where he worked for the British bank Hirsch & Co., in 1911 Jacques started a banking house, Jacques de Gunzburg et Cie, taking on his nephew Jean de Gunzburg, son of Salomon, to work with him. A connoisseur of the workings both of the Bourse de Paris and of foreign markets, he invested in mining (Compagnie française des mines d’or de l’Afrique du Sud-Cofrador) and energy sectors (Société générale d’électricité, Westinghouse). Jacques was also a co-founder of the Société de l’Hôtel Ritz, of which he was financial director.

In 1901 the merger of the Banque d’Afrique du Sud and the Banque internationale de Paris resulted in the creation of the Banque française pour le commerce et l’industrie, of which Jacques de Gunzburg was appointed a director. He was also among the investors who contributed to the creation of the Crédit franco-égyptien in 1907. In 1910 he was awarded the Légion d’honneur for his role in bringing about France’s closer relations with Japan and Brazil, two countries whose industrial economies were expanding rapidly.

Little is known of Jacques’ private life. In 1902 he married Quêta de Laska, who had recently divorced the jeweller Germain Bapst, and they had a son Nicolas (Nicky), who would become a leading figure in Parisian café society and the celebrated editor of Vogue. Jacques was a member of the Cercle de l’Union interalliée and a founder of the Golf de Dieppe golf course – for a while he owned a house at Pré-Saint-Nicolas, built in orientalist style by his diplomat friend Count Gaston de Saint-Maurice, now destroyed. His generosity towards family members is well documented: he paid the debts of his uncle Gabriel de Gunzburg and contributed towards the marriage of his niece Olga de Gunzburg in Paris in 1921.

Jean de Gunzburg (26 November 1884, Paris–28 November 1959, Paris)

The third child of Salomon de Gunzburg and Henriette Goldschmidt, Jean grew up in Paris but kept his Russian nationality, faithful to the wishes of his grandfather Joseph Evzel de Gunzburg, and returned to Russia to complete his military service. As a graduate of HEC (Ecole des hautes études commerciales de Paris), he was destined for a career in banking, honouring tradition on both sides of his family: having worked briefly for Westinghouse, he joined his cousin’s banking house, Jacques de Gunzburg et Cie.

On 26 August 1914 he volunteered for the Foreign Legion for the duration of the war. As an interpreter for the French military mission with the British Army, he was posted to the front in March 1915 as an interpreter attached to a field artillery group. Decorated with the Croix de guerre, at the war’s end he requested, and was granted, French naturalisation. In March 1924 he married Madeleine Hirsch, daughter of the banker Louis Hirsch. Jean moved to work in his father-in-law’s bank, becoming Hirsch’s associate in 1926 then his successor, as co-director with his brother-in-law André Louis-Hirsch. With a preference for industrial investment, he was notably one of the creators of CSF (Compagnie française de télégraphie française, later Thomson), of which he became one of the directors.

In the autumn of 1940, after a short stay on the Basque coast, Jean moved with his wife and three children – Alain (b.1925), François (b.1927) and Pierre (b.1930) – and his mother-in-law Alice Hirsch to Châtel-Guyon, not far from Vichy, where the Hirsch bank had based itself when the occupied zone was established in northern France. He made efforts to prevent the Aryanisation of the bank, emphasising its existence since the 18th century and its long-term commitment to support the French state, and recalling the distinguished military service of members of both the Gunzburg and Hirsch families: David Hirsch had fought in Napoleon’s army at Waterloo, he himself was a veteran of 1914–18, and his brother-in-law André had been taken prisoner in 1940 and sent to a POW camp in Germany. But it became too risky to remain, and in June 1942 Jean, Madeleine, their children and Jean’s mother-in-law obtained a permanent visa for the United States and they moved to New York. Their Paris apartment in the Avenue du Maréchal Fayolle was requisitioned by the German Navy. Their son Alain joined the Free French, reached England and went to the Ecole des Cadets de la France libre. Through 1944 and 1945 he took part in the military liberation of France and Germany. After the war both he and André Louis-Hirsch made numerous approaches to the Commission de récupération artistique to seek reparation for property looted by the Nazis.

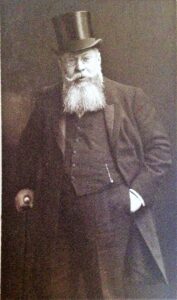

Joseph Evzel de Gunzburg (4 January 1813, Vitebsk–12 January 1878, Paris)

The founder of the J. E. Gunzburg bank, Joseph Evzel Gunzburg was the architect of an extraordinary economic and social ascent which made him one of the wealthiest men in tsarist Russia. In 1874, following his son Horace, he received the title of baron, granted by the prince of Hesse-Darmstadt in recognition of financial services rendered. Tsar Alexander II subsequently recognised the title and made it hereditary, but several decades later Nicolas II retracted the recognition, refusing to include the barons de Gunzburg among the Russian Empire’s hereditary nobility.

A leading actor and moderniser in the great Russian century, Joseph Evzel remained loyal to the Jewish traditions of his family, descended from a distinguished line of rabbis and businessmen originating from Günzburg in Swabia. He grew up in Vitebsk with his sisters Eleone and Bella, in the Russian Empire’s Pale of Settlement. His parents, Gabriel Iakov Gunzburg and Léa Rashkes, gave him a thorough religious education in the Vilnius tradition (his father’s home town). His marriage to Rassia (Rosa) Dynin, the daughter of the postmaster in Orsha, south of Vitebsk, produced five children: Alexandre (b.1831), Horace (b.1832), Ury (b.1840), Mathilde (b.1844) and Salomon (b.1848). He was soon brought in to help his father in his business affairs, successfully expanding the Gunzburg trading agency in Kamenets-Podolsk; in 1833 he became a merchant of the First Guild. Deciding to concentrate on the drinks industry, to begin with he worked as supervisor for a Polish nobleman who owned breweries and subsequently as a manager for Alexander Borozdin, owner of an alcoholic beverage concession in Kamenets-Podolsk, before himself becoming an otkup (concessionaire) in 1839 for numerous districts in the Pale of Settlement. In recognition of his business skills and contribution to the Russian treasury, he was awarded the title of “honorary citizen” in 1849. Contracted to supply vodka and beer to the imperial armies during the Crimean War, he was awarded the Order of Saint Andrew “for zeal” by the tsar in 1856, who later granted him the high-ranking title of “commercial counsellor” in 1874.

In tandem with his business activities Joseph Evzel was a tireless defender of the rights of his co-religionists. In 1850 he sent to the imperial administration a “Note Regarding the Situation of of the Jewish People in Russia” which proposed measures to enhance the freedom to settle and access to training, education and agriculture. In 1859 he was among the Jewish businessmen who secured official permission from Tsar Alexander II for Jewish merchants of the First Guild to live outside the Pale of Settlement. Subsequent petitions extended this permission to university graduates (1865), craftsmen (1865) and former soldiers (1867). As a result, in 1859 Joseph Evzel moved to to the Russian capital where, with the wealth accumulated from his success in the production and sale of alcohol, he opened the J. E. Gunzburg bank, one of Russia’s first private banks to be linked to European financial institutions. The Russian government was a major client. Gunzburg’s bank invested in railway-building and in the development of sugar production in Ukraine, where Jospeh Evzel had substantial landholdings. He diversified into insurance and local deposit banks and invested in the Lena goldfields in western Siberia, where he owned a shipping company on the Sheksna river. He also owned land and forests in Bessarabia.

Joseph Evzel’s move to Russia’s capital culminated in the official establishment of a Jewish community in St Petersburg, which he led and of which he was one of the main founders, negotiating with the authorities for, among other things, the construction of a synagogue (completed in 1893). His commitment to philanthropy led him to co-found the Society for the Promotion of Culture (OPE) in 1863 to promote the social and linguistic integration of Jews in Russian society. The “Gunzburg office” in St Petersburg provided financial help for Jewish students in the capital; among them was the sculptor Marc Antokolsky. Joseph Evzel’s struggle for civil equality also led him to press for Jews to be included when universal military service was introduced in 1874.

After a journey to Paris in 1857, the French capital, and France, became a lasting second home for the Gunzburg family, who, despite the reforms Joseph Evzel had helped bring about, still faced daily pressures, as all Jews did, in tsarist Russia. In 1862 Joseph Evzel had the satisfaction of marrying his only daughter Mathilde to Achille Fould, the nephew of Napoleon III’s famous finance minister. Five years later he opened a subsidiary of the J. E. Gunzburg bank in Paris, entrusting its management to his son Salomon. In 1869 he moved with his children and grandchildren to a lavish town house he had had built at 7 Rue de Tilsitt in the new district of Place de l’Etoile, and two years later he acquired a country residence at Saint-Germain en Laye by buying the former headquarters of the French imperial guard. When he died in 1878, at the age of sixty-five, France’s chief rabbi Lazare Isidor paid tribute to the charisma of a “tireless champion of the Jewish cause”, who chose to be laid to rest at Montparnasse cemetery (where the Gunzburg family has a funerary chapel), but who in his will urged his descendants to remain faithful to their homeland of Russia and to their Jewish religion. While he was alive he had included his son Horace in all his affairs: after his death Horace loyally continued his father’s work.

Horace (Naftali Herz) de Gunzburg (25 December 1832, Zvenigorodka–2 March 1909, St Petersburg)

The second son of five children, Horace was his father Joseph Evzel’s named heir: at the latter’s death, he became the new head of the family, continuing to pursue his professional as well as community and philanthropic activities with great success. He was a hard worker, balanced and reflective by character, and developed into a leading figure in St Petersburg life in the second half of the 19th century, as his official titles of state councillor, member of the council of commerce and manufacturing, member of the stock market council and the municipal council. As his father’s colleague at the J. E. Gunzburg bank, he was also his father’s executor at his death in 1878 and fourteen years later oversaw the bank’s closure in 1892. He lived and worked at his impressive residence at 17 Konnogvardeysky Boulevard, where he held business meetings, community meetings, and all kinds of musical and fund-raising evenings. The rules of the kashrut and shabbat were strictly observed there, bringing a dignified example of active Jewish practice into the heart of Russian high society. After his wife Anna’s death in 1876, he took personal charge of the upbringing of his eleven children.

In the philanthropic arena Horace took a leading role, even as the Russian political, economic and social situation became increasingly tense. From 1881 he set up an office to offer aid to the victims of pogroms and was the unofficial but effective representative of the Alliance israélite universelle at a time when it was a proscribed organisation on Russian soil. To defend Jews who were the victims of numerous acts of violence and discrimination, the banker enlisted the help of the legal expert Emmanuel Levine and the lawyer Heinrich Sliozberg. In 1882 they succeeded in alleviating the “Temporary regulations”, also known as the “May laws”, which limited the economic rights and rights of residence of Russian Jews. When the government was persuaded to set up the Pahlen Commission on the Jewish Question in 1883 to investigate mass expulsions of Jews from their villages and review existing laws relating to Jews, Horace became a consultant member, and like his father he was involved in educational development as a founder of ORT (Society for Agricultural and Artisanal Labour). Horrified by the continuing rise of anti-Semitism, he wrote a long letter to Tsar Alexander III (16 May 1890) defending the rights of Jews. The “Gunzburg circle” worked ceaselessly, often behind the scenes, with the various Russian administrations to defend the rights of Russian Jews, but they were unable to prevent the erosion of Jewish living conditions and the rise of anti-Semitism at all levels of Russian society. By 1892 Horace had lost the right to his seat on the St Petersburg municipal council, and was unable to obtain any support from the Russian state to rescue the J. E. Gunzburg bank when it fell into difficulties as a result of the economic crisis.

Horace de Gunzburg’s social involvement was not limited to the Jewish community. He was treasurer and principal benefactor of the Society of Russian Artists in Paris. With the backing of the writer Ivan Turgenev, the painters Alexei Kharlamov and Alexei Bogoliubov and the sculptor Marc Antokolsky, the society supported Russian artists by buying their work and organising exhibitions to make them better known by the Parisian public. In St Petersburg he helped both Jewish and non-Jewish artists, forging personal links with the art critic Vladimir Stasov, the composer Anton Rubinstein, the painter Ivan Kramskoi and the sculptor Ilia Gintzburg (no relation). Horace also supported research such as the work of Daniel Khvolson on the allegations of ritual murder in the Kutaisi affair of 1879 and the writings of Sergei Bershadskiy on the Jews of Lithuania. Horace endowed a renowned surgical unit at the Stock Market Hospital, donated to St Petersburg’s Institute of Experimental Medicine (modelled on Paris’s Institut Pasteur), founded a society for low-cost housing for female students on the highly regarded Bestuzhev courses and women’s courses in medicine. Politically liberal, Horace was close to the circle of the Messenger of Europe founded by Mikhail Stasiulevich. Convinced of the importance of a free press, he backed the publications of Alexander Zederbaum both in Russian and Hebrew. He had deep friendships with writers of great talent such as Ivan Goncharov and the philosopher Vladimir Soloviev. For his 70th birthday in January 1903, which coincided with the 40th anniversary of his leadership of the Society for the Promotion of Culture (OPE), Horace’s family, friends and colleagues organised a series of public and private celebrations. The famous expedition to collect ethnographic evidence of the culture of the shtetl organised by S. Ansky and financed by Vladimir de Gunzburg was named in his honour the Baron Horace de Gunzburg Expedition.

Mathilde Fould née Mathilde de Gunzburg (21 July 1844, Kamenets-Podolsk–3 June 1894)

Khaya-Matla (who became Eve Mathilde in France) was the fourth child and only daughter of Joseph Evzel de Gunzburg and Rosa Dynin. Born in Kamenets-Podolsk (Kamianets-Podilskyi in modern Ukraine) in the Russian empire’s Jewish zone of residence, or Pale of Settlement, she was twelve years old when her parents settled in Paris. Her education in Paris was partly supplied by her cousin and sister-in-law Anna, her brother Horace’s wife, whose charm and intelligence greatly eased the Gunzburgs’ acceptance into Parisian society. Joseph Evzel was proud of his daughter, who was an enthusiastic learner, notably of music (piano) and languages (besides French, English and Italian, she worked hard to improve her Russian and German). It’s likely she also knew the basics of Hebrew, because for her fifteenth birthday her father’s librarian, Senior Sachs, took the trouble to compose a delightful verse tribute to her in Hebrew, “Le-Yom Huledet”.

When she was eighteen, Mathilde Gunzburg married Paul Fould on 11 March 1862. A photograph by Adam Salomon shows the young bride in crinoline and gathered ribbons typical of the era of Napoleon III. With a dowry of 2.22 million francs, equivalent to 8,050,522 euros, the bride’s fortune was in line with the Gunzburg family’s multimillionaire reputation. Palu Fould was the nephew of Napoleon III’s finance minister, Achille Fould, and son of Emile Fould, a Paris notary and the first Jew to qualify in the profession. Following in his father’s footsteps, Paul was a “handsome, intelligent, distinguished young man, an auditor at the Council of State”. The marriage reinforced the Gunzburg bank’s position in European finance circles as an establishment made more trustworthy by its international network of associates. Mathilde’s marriage contract, signed by around a hundred witnesses (Furtado, Oppenheimer, Koenigswarter, Stern, Halphen, Hollander, Weisweiller, Rodrigues Henriquès, Goldsmith, Ellisen, Beer, Sarchi, Pereire…), reflected the two families’ social acceptance. Mathilde and Paul’s marital alliance marked the Gunzburgs’ entry into the Parisian Jewish haute bourgeoisie, a milieu then still in the process of defining itself. The Rothschilds were absent, but their absence is easily explained: the Foulds belonged to Napoleon III’s imperial circle, whereas James de Rothschild and his descendants, particularly active during the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe I, were still showing their Orléanist sympathies. A rapprochement was only a matter of time, however: one of Paul and Mathilde’s granddaughters married Edouard de Rothschild in 1905.

Mathilde had done well with her in-laws: her father-in-law was “an excellent man, simple, liked by everyone, hospitable, easy-going”. Her mother-in-law, Palmyre née Oulman, though authoritarian, was an intelligent woman. The future should have smiled on the young couple, but Mathilde’s health started to decline with her first pregnancy, according to Louise, the Foulds’ eldest daughter, born in 1862, and although she gave birth to two more daughters, Suzanne (1867) and Marie (1870), her ill health distanced her from normal social relations. She was frequently bedridden and spent long periods at spas and in the south of France, while her husband found consolations outside the family home. Mathilde found support in her mother Rosa Gunzburg, a pious woman who was deeply attached to Jewish traditions and isolated in the Gunzburgs’ Parisian world, in which most of the customs and manners were foreign to her.

Having moved to 138 Avenue des Champs Elysées, the young Foulds remained in daily contact with Mathilde’s family on Place de l’Etoile. During the war of 1870 between France and Prussia, because he enjoyed freedom of movement as a foreigner, Joseph Evzel was able to evacuate his granddaughters to Menton. Moved by the plight of the French soldiers, he turned his house in Rue de Tilsitt into a military hospital and handed it over to Paul Fould to run.

On her father’s death in 1878, Mathilde contested the “special supplementary will written in French” in which Joseph Evzel gave her his house in Paris at Rue de Tilsitt, a capital of one million francs for the education and establishment of her children, and a life annuity of 50 thousand francs per annum. With her husband’s help, she held out for her rights of succession in totality, including her father’s assets and businesses located in Russia. She reached an eventual compromise with her brothers Horace, Ury and Salomon de Gunzburg: to the 2 million francs of dowry payable that year, a further 1 million francs was to be paid in 1881 (by part-mortgaging the lands in Bessarabia), plus a lifetime annuity of 50,000 francs, and a commitment to pay to Mathilde’s heirs 811,000 francs after her death. She further agreed to sell her brothers the rights and shares that she owned in the saltworks at Chongar (now Chonhar) in Crimea for 1 million francs, and ceded the securities held in her account at the Gunzburg bank, with the exception of her shares in the shipping company on the Sheksna river. Mathilde thus inherited from her father approximately 5 million francs, and at the death of her mother in Paris in 1892 also received an inheritance from her, though she herself died soon after, in 1894.

Being French by marriage, Mathilde saw her daughters accepted into French high society. Louise married the banker Emile Halphen and had two daughters of her own: the elder, Germaine, married Edouard de Rothschild in 1905, and Alice married Maurice de Brémond d’Ars in 1914. Suzanne, who married the industrialist Raoul Gradis, had three children, Gaston, Jean and Marie-Louise. From the marriage of the youngest daughter, Marie, to Henry de Courcy were born Antoinette, who married Antoine de Gramont, Duke of Lesparre, in 1921, and Aimery, who died in combat in 1916.

As heirs to part of the immense Gunzburg fortune before it disappeared in the chaos of the Russian Revolution and the Red Terror, Mathilde’s descendants carried on the philanthropic commitment of the women of the family. Louis Halphen (1862–1945) played an important part in the creation of the Fondation Emile Halphen at 31 Passage Ménilmontant, set up to fight infant mortality by ensuring the best care for mothers and babies. In 1922 she created “Protection for the new-born” (La protection du nourrisson), a network of dispensaries for pregnant women and babies in the Seine département. As the author of a fascinating volume of “Mémoires”, Louise also contributed substantially to the passing-on of the family’s history.

Nicolas de Gunzburg (“Nicky”) (12 December 1904, Paris–20 February 1981, New York)

The only son of Baron Jacques de Gunzburg and the Polish-Brazilian Quêta de Laska, Nicolas, known as Nicky, was born in Paris. A declared homosexual and leading figure in café society, he left his mark on his time with incomparable style as a symbol of masculine elegance.

His father Jacques had been the favourite grandson of Baron Joseph Evzel de Gunzburg, founder of the family dynasty and bank, and had himself become an international banker of stature. Fifty-one years old when his only son was born, Jacques brought Nicky up in considerable comfort between London, Paris (10 Avenue Bugeaud then 14 Avenue des Champs Elysées) and the seaside resorts of Normandy. Though Nicky’s childhood lacked for nothing materially, one senses it was less than happy on an emotional level. He remembered being taken to the Ballets Russes, the influential ballet company founded by Serge Diaghilev and sponsored by his father’s cousin Dimitri de Gunzburg, a well-known dandy. His mother Quêta had been married before, to Germain Bapst, art historian and bibliophile, and had a daughter from that marriage, Audrey Manuela Alexandre Joaquina Bapst, born in 1892. Quêta’s marriage to Jacques de Gunzburg was no more a success than her first. She rapidly divorced hims to marry her third husband, Prince Basil Naryshkin, before sadly descending into severe mental illness.

Losing his mother in 1925 and his father in 1929, Nicky not only came into a reasonable fortune but found himself free of the conventions of family life. He became the inspiration for one of the characters in Edouard Bourdet’s 1932 play La Fleur des Pois, which dramatised the lives of the homosexuals of Paris’s smart set, and he is said to have been the reason for the fashion designer Lucien Lelong creating the famous perfume that he called “N”, in homage to Nicky rather than to the Russian princess Natalia Paley with whom he had a marriage of artistic convenience.

Living in high style, Nicky rode in a Rolls-Royce with a Russian ex-colonel as his chauffeur. He was a fixture at Parisian balls of the 1920s and 1930s. In 1927, at the “Bal Proust” hosted by Jean-Louis and Baba de Faucigny-Lucinge, Nicky, dressed as a bellboy from the hotel at Balbec, partnered the Comtesse de Brantes, and at the “Bal des Entrées de l’Opéra” he paired with the Surrealist artist Valentine Hugo to make a romantic couple. In June 1929 he only missed the famous “Bal des Matières” given by Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles because he was on a business trip to New York. In 1931 he and Elsa Maxwell, the American gossip columnist, welcomed guests for a “fête champêtre” (garden party) in the little house (now demolished) that he rented from the city of Paris near the racetrack at Longchamp. His friend the painter Christian Bérard, then working with Christian Dior, organised its transformation, draping the building in blue satin and turning it into an 18th-century pavilion. Hay wains, heaped-up vegetables and flowers, and life-size papier mâché animals completed the decor. In 1934 Nicky threw himself into organising another festivity with his friends Jean-Louis and Baba Faucigny-Lucinge, on the island in the Bois de Boulogne, for the “Bal des Valses” (The Ball of the Waltzes), also called “Une Soirée à Schönbrunn”. Jean-Louis dressed up as Emperor Franz Joseph, Baba as Empress Elisabeth, and Nicky as Archduke Rudolf. The costumes were designed by Christian Bérard and sewn by Karinska, the dressmaker of the Ballets Russes. Before the party the hosts and their guests were immortalised by Horst P. Horst in the studios of Vogue, Nicky looking especially brilliant and sulphurous, with his gleaming decorations like so many jewels and his eyes outlined in kohl. Horst, then a young photographer at French Vogue, later also immortalised him in a striped tennis outfit.

In the early 1930s Nicky de Gunzburg also launched himself on an acting career, under the name of Julian West to avoid criticism from his family. In the film Vampyr, or the strange adventure of Allan Gray (1934), directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer, he played the title role; his involvement ultimately turned out to be also financial, as investor and producer.

Just turned thirty, Nicky then decided to emigrate to the United States with his friends Fulco di Verdura and Natalia Paley, first settling in Hollywood where he played some walk-on parts for Fox. In 1936, with his companion the actor Erik Rhodes, he moved to New York to start what turned into a dazzling career as editor at Harper’s Bazar and Town & Country and senior fashion editor at Vogue, where, in 1949, he became the loyal colleague of Vogue’s editor-in-chief, Diana Vreeland, who later declared that she owed him everything in matters of taste. Highly regarded by Alexander Liberman, editorial director at Condé Nast Publications, Nicky championed the career of notable fashion designers such as Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta and Calvin Klein. Often short of funds himself, he nevertheless managed to buy a small island at Highland Lake, New Jersey, where he had a wooden house built. Hemlock Island was his refuge, where he liked to ski and ice skate as he had in his childhood, to have friends to stay, and above all spend happy times with his partner Paul Sherman (1926–1985), illustrator and publicist. After losing his job at Vogue when Diana Vreeland was fired in 1971, Nicky de Gunzburg worked for Calvin Klein, who saw in him a mentor, both men sharing the idea of elegance expressed in a refinement that was discreet, practical and modern.

In New York, Nicky would spend time with several members of the Gunzburg family who had found refuge in the United States when fleeing from Nazism, among them his aunt Yvonne de Gunzbourg and cousin Théodore de Gunzburg. When he died and was buried at Glenwood cemetery, close to his house in New Jersey, Calvin Klein delivered the elegy, accompanied by Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta.

Philippe de Gunzbourg (17 February 1904, Paris–10 July 1986)

Philippe was the eldest child of Baron Pierre de Gunzbourg (1872–1948) and Yvonne Deutsch de la Meurthe (1882–1969). A leading resistant during the Second World War, he afterwards became an agricultural businessman in the Southwest of France.

Philippe had lukewarm memories of his pampered childhood with his sisters and brother, Béatrice (1906–1925), Cyrille (1910–1932) and Aline (1915–2014), in the family home at 54 Avenue d’Iéna and the house at Garches near the golf course of Saint-Cloud. He was uncomfortable with, then critical of, a lifestyle that he felt was too luxurious, and he also found it difficult to reconcile his French and Russian origins. Much liked by his maternal grandfather, the industrialist Emile Deutsch de la Meurthe, he benefited from the latter’s advice and affection. On the Gunzburg side, his father was a man of rare elegance who passed on his anglophilia. In the company of his Russian uncles, exiled to Paris after the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, he discovered the pleasures of the city’s nightlife. As a young man of considerable good looks, he fell in love with Gabrielle Berteau, one of the last of Paris’s demi-mondaines, then in her forties, and married her, to his parents’ great consternation. The couple had a civil marriage in Marrakesh in 1929, followed by a religious ceremony in Paris for disparate faiths. Philippe’s parents nevertheless helped them buy a twenty-hectare farm at Saint-Varent in the Deux Sèvres département, where they started horse-breeding. Two family tragedies caused Philippe to call his pleasure-seeking lifestyle into question: first the death of his sister Béatrice on 4 June 1925, the victim of a riding accident in Windsor Great Park, then the death of his brother Cyrille on 20 January 1932 at Briançon, from the after-effects of pneumonia caught while he was doing his military service as a corporal scout in the 159th Alpine skiing regiment. Reconnecting with his family, Philippe established a new, highly affectionate bond with his sister Aline, eleven years his junior. After breaking up with Gabrielle, in 1934 he married Antoinette Kahn, a young woman from his own milieu, and moved to Avenue d’Iéna. The couple had four children: Patrice (1936–1991), Jacques (1939–2022), Hélène (b.1947) and Alix (b.1948).

Faced with the 1930s’ rising anti-Semitism, Philippe was increasingly conscious of his Jewish identity. When war broke out, he was immediately concerned about the risks that a Nazi victory would pose. He served first as a nursing orderly then as a liaison agent on the Maginot line in 1940. When France fell, he decided to settle in the free zone. In January 1941 he bought a small farm called Le Barsalous at Pont du Casse in the Lot-et-Garonne, doing his best to look like a well-off Parisian taking refuge in the countryside. Doing so made him able to welcome friends and members of his family: after escaping from the Netherlands, Hélène Berline, his uncle Sacha de Gunzburg’s youngest daughter, stayed with him for a long time with her husband and children. Philippe was in contact with a young rabbi and helped those who were under the rabbi’s protection, thanks to the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (Organisation for Saving the Child)). He also joined the UGIF (Union générale des Israélites de France), not knowing that this organisation had been put in place by the Vichy regime to identify Jews living in France. Having helped his parents and sister Aline flee to the United States, he noted, at a distance, the dispossessions of family properties that were going on in Paris and the organised looting of Jewish property that was being carried out by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR (Reichsleiter Alfred Rosenberg’s action team)). He was personally affected, because the offices that were administering the Nazi “Operation Furniture” (Möbel Aktion) were located at 54 Avenue d’Iéna, the home of Pierre and Yvonne de Gunzbourg.

Philippe’s next step was to join the Resistance in the Southwest against the Vichy government and German occupiers. In 1942, he was contacted by Maurice “Eugène” Pertschuk acting on behalf of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), formed to conduct and facilitate espionage, sabotage and resistance in German-occupied Europe. His status as a Parisian taking refuge at Le Barsalous served as cover for him (his code name was “Philibert”) in the Prunus network. His wife Antoinette and a courageous English nurse, Alice Joyce, helped him rendezvous with British secret agents parachuted in by the Allies, and hide them, along with parachuted messages and weapons, sometimes taken from place to place in a baby carriage. Antoinette was also an occasional vital liaison person who could meet, at one of the restaurants in the town of Agen, SOE officers without attracting the attention of the local police.

After Pertschuk’s arrest on 12 April 1943 (he was sent to Buchenwald, where he was executed), Philippe met George “Hilaire” Starr, a new SOE agent for whom he became the linchpin in the Dordogne for the Wheelwright network (new code name “Edgar”). With Starr he learned to to assemble plastic explosives, organised sabotage operations at rail junctions (Eymet, Bergerac), and formed dozens of small groups of resistants to receive parachuted agents and weapons. While he was doing this, he also managed to arrange for Antoinette and their children to cross into Switzerland to ensure their safety. He now lived in strictly clandestine conditions, never staying two nights in the same place and moving around the Dordogne and then Lot-et-Garonne by bicycle, backed by André Ruff, his young number two and bodyguard. He escaped being caught by the Gestapo several times, relying on his survival skills and knowledge of the terrain. In the spring of 1944, during the battles to liberate France, SOE agents coordinated resistance across an area running from Bergerac to Sarlat and from Toulouse to Auch. In the days following 7 June, Resistance networks succeeded in slowing the advance of the 2nd SS Panzer Division “Das Reich” that was heading for Normandy. In reprisal the SS committed many massacres, the worst of which was at Oradour sur Glane. It was a period of intense combat, and Philippe helplessly witnessed the death of several of his men.